We have a range of legal issues concerning the Trump’s tariff case before the Supreme Court. For example, separation of powers and the ‘major question doctrine. But the one primary issue that is on everyone’s mind is without a doubt — Will politics of the conservative majority override careful legal analysis of the statute (IEEPA) and presidential authority? This question is wide open. So is the role of Congress in setting tariffs, presidential foreign affairs and the role of courts in reviewing such issues.

……………………………………………….

- “Neal Katyal, a “prominent litigator” and former acting solicitor general who “has argued more than 50 cases at the Supreme Court,” will argue there again next week on behalf of small businesses that challenged Trump’s authority to impose tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act …. Katyal won the job through “a coin flip” over Pratik Shah, the head of Akin Gump’s Supreme Court practice. “We are honored to be represented by Neal at this important moment in the case and are putting all our energy into preparing for the hearing in Nov. 5th.” “Katyal to Argue Tariff Case Before Supreme Court.” SCOTUS Blog (10.29.25).

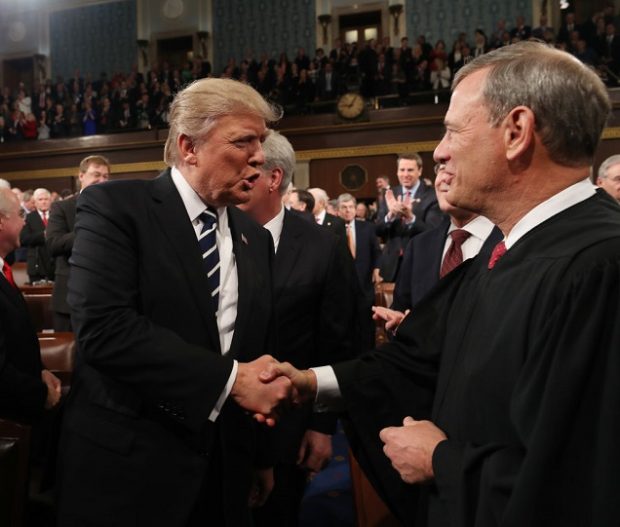

- “Ahead of next week’s oral arguments on tariffs let’s look behind the scenes of an interesting, related case: Dames & Moore v. Regan. In it, the court considered the president’s authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (the same policy that’s at issue in the tariffs dispute) to use frozen Iranian assets to resolve the Iranian hostage crisis. Chief Justice John Roberts, then a clerk for Justice William Rehnquist, helped write the court’s decision in favor of the president. The justices are expected to revisit Dames & Moore as they weigh whether IEEPA authorizes President Donald Trump’s tariffs.” “Dames & Moore and Trump’s Tariff Case.” Scotus Blog (10/30.25).

- “Tariffs or taxes on imports have been a powerful weapon in Donald Trump’s trade policy in his second term, but could they be illegal? The United States Supreme Court will next week start to hear a case that challenges the president’s right to impose those duties without the approval of Congress. Defeat for Trump could have major ramifications for US trade policy. Victory could give the president broad new powers, not just over tariffs. Which way is the case likely to go? And what will Trump’s options be if he loses? …. It’s going to be really hard for the court to actually write an opinion that says that this particular statute, the International Economic Emergency Powers Act, or what we call often, IEEPA, actually provides the tariff authority that the president has claimed …. This statute grew out of something called the Trading with the Enemy Act, and the idea was that during times of war, you needed to give the president particular powers over trade …. So Trump is doing something that has never been done. The statute that he’s using was passed in 1977. So in its, you know, 50-plus history, it has never been used to impose tariffs. It has been used repeatedly to impose economic sanctions, particularly financial sanctions on transactions …. If the Congress disagrees with the president’s use of this particular authority, the law gives the Congress the ability to pass a resolution that terminates the emergency …. But built into the law was this notion that either the House or the Senate in the United States could pass a resolution saying, we disagree. We therefore terminate the emergency …. In Yoshida, the court was very clear that we will allow these tariffs because they were very limited in time. They were very limited in the scope of what they covered. They only established tariff levels that were already below the level that the Congress itself had established for tariff levels …. Trump’s view is, as long as you’re under that foreign affairs national security tent, their view is the president has unlimited powers and that the courts should not, could not scrutinize anything that the president does in the realm of foreign affairs, national security …. This is a very conservative court and they have ruled in many instances in Trump’s favor. But I think a couple things are different here …. And at some level, the court, I think has to take on board those basic facts that the word tariff and duty do not appear anywhere in this statute …. All of those other statutes require, again, an evidentiary finding and they are typically both product- and country-specific. And again, the president would have to show that they have met the terms of each one of those individual statutes for each one of the products, each one of the countries, in order to uphold any tariffs that they might impose under them …. The particular national security exception, Article 21 of the GATT, was itself fairly limited. I mean, yes, it said that you could declare what was in your own essential security interests, but in theory, you could only take exceptions if what was involved was trade in nuclear materials or arms, ammunition, implements of war …. What everybody is complaining about is the chaos, is the uncertainty, the inability to plan …. That level of predictability, instability, insecurity within the trading system is something that over the long haul is intolerable. And therefore, I do think you’re going to see more and more of the broadly writ business community say, we cannot live with this level of chaos. We need more of a rules-based system.” “Are Trump’s Tariffs Legal (Jennifer Hilman).” Financial Times (Oct. 30, 2025).

“How did the dispute over the tariffs start? Beginning in February, Trump issued a series of executive orders imposing tariffs. The tariffs can be divided into two categories. The first type, known as the “trafficking” tariffs, targeted products of Canada, Mexico, and China, because Trump says those countries have failed to do enough to stop the flow of fentanyl into the United States. The second category, known as the “worldwide” or “reciprocal” tariffs, imposed a baseline tariff of 10% on virtually all countries, and higher tariffs – anywhere from 11% to 50% – on dozens of them. In imposing the worldwide tariffs, Trump cited large trade deficits as an “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and economy of the United States.” One case was filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia by Learning Resources and hand2mind, two small, family-owned companies that make educational toys, with much of their manufacturing taking place in Asia. Another case challenging the tariffs was brought in the U.S. Court of International Trade by several small businesses, including V.O.S. Selections, a New York wine importer, and Terry Precision Cycling, which sells women’s cycling apparel. What are the laws at the center of the dispute over the tariffs? Article I of the Constitution gives Congress the power to “lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises,” and it requires that “Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives.” In issuing the executive orders that imposed the tariffs, Trump relied primarily on a 1977 law, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act. Section 1701 of IEEPA provides that the president can use the law “to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States,” if he declares a national emergency “with respect to such threat.” Section 1702 of the act provides that, when there is a national emergency, the president may “regulate … importation or exportation” of “property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest.” Has the Supreme Court addressed this question? The Supreme Court has not weighed in on the president’s power to impose tariffs under IEEPA. United States v. Yoshida International, a 1975 decision by the U.S. Court of Customs and Patent Appeals, is perhaps most relevant to the current tariff debate because of the similarities between IEEPA and the text of the law at the center of that case, the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917. That case began as a challenge to then-President Richard Nixon’s imposition of a 10% temporary tariff on imports in response to a large trade deficit, which in 1971 was a relatively unusual development in U.S. history. In 1974, the U.S. Customs Court – the predecessor to the Court of International Trade – ruled that Nixon did not have the power under the Trading with the Enemy Act, which allowed the president in the case of an emergency to “regulate … the importation … of … any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest.” In response to the ruling by the Customs Court, a provision of the Trade Act of 1974 specifically gave the president the power to impose tariffs to “deal with large and serious United States balance-of-payment deficits,” but – at the same time – the law limited tariffs to a maximum of 15% and a duration of five months. The Court of Customs and Patent Appeals reversed the decision of the Customs Court, concluding that Nixon had the authority to impose the tariffs after all. The 10% tariff, the court explained, was a “limited” one imposed “as ‘a temporary measure’ calculated to help meet a particular national emergency, which is quite different from ‘imposing whatever tariff rates he deems desirable.’” What are the challengers’ arguments? The challengers contend that – unlike other laws that directly deal with tariffs – IEEPA doesn’t mention tariffs or duties at all, and that no president before Trump has ever relied on IEEPA to impose tariffs. And the government has not provided an example of any other law, they add, in which Congress used the phrase “regulate” or “regulate … importation” to give the executive branch the power to tax. Interpreting IEEPA to give the president the power to impose unilateral worldwide tariffs would create a variety of constitutional problems, the challengers before the Federal Circuit also contend. First, they write, it would run afoul of a doctrine known as the major questions doctrine, they say, which requires Congress to be explicit when it wants to give the president the power to make decisions with vast economic and political significance. Allowing the president to rely on IEEPA to impose the tariffs would also violate the nondelegation doctrine – the principle that Congress cannot delegate its power to make laws to other branches of government. How did the lower courts rule on these cases? In the cases brought by V.O.S. Selections and the other small businesses as well as the states, the CIT on May 28 ruled for the small businesses and the states, and it set aside the tariffs. The CIT reasoned that IEEPA’s delegation of power to “regulate … importation” does not give the president unlimited tariff power. The limits that the Trade Act sets on the president’s ability to react to trade deficits, the court continued, indicates that Congress did not intend for the president to rely on broader emergency powers in IEEPA to respond to trade deficits. The “trafficking” tariffs are also invalid, the CIT continued, because they do not “deal with an unusual and extraordinary threat,” as federal law requires. Instead, the CIT concluded, Trump’s executive order tries to create leverage to deal with the fentanyl crisis. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which hears appeals from the Court of International Trade, put the CIT’s ruling on hold while the government appealed. By a vote of 7-4, a majority of the Federal Circuit agreed that “IEEPA’s grant of presidential authority to ‘regulate’ imports does not authorize the tariffs” that Trump had imposed. In the case in federal court in the District of Columbia, U.S. District Judge Rudolph Contreras ruled for Learning Resources and hand2mind, agreeing with them that “the power to regulate is not the power to tax.” Contreras’ order was a narrow one, barring the government only from enforcing the tariffs against Learning Resources and hand2mind, and he put that decision on hold while the government appealed. “ “Trump’s Tariffs – Summary of Case.” Scotus Blog (10.30.25).

“Five Republicans join Democrats to repeal the 50% border tax on Brazil …. It’s good to see some Members of Congress push back against Trump’s usurpation of their constitutional power over trade and taxes …. The Supreme Court next week will hear a challenge to Trump’s use of IEEPA …. The Senate vote is a welcome signal that he won’t get it.” “Senate Stirs Against Tariffs.” Wall Street Journal (Oct.31, 2025).

“Trump’s approach to world affairs is deeply transactional …. For large parts of the world, it is Trump’s tariff policies that are now the single most important aspect of their relationship with the US. …. It is probably too much to expect that an instinctive and egotistical figure like Trump will ever come up with a fully formed and internally consistent approach to the outside world.” “The Trump Doctrine.” Financial Times (Nov. 1, 2025).

“This momentous case must either undermine or buttress the Constitution’s architecture: the separation of powers. Six amicus briefs explain why …. The conservative Goldwater Institute and the liberal Brennan Center separately argue that the statute the president says gives him unreviewable power to impose taxes (which tariffs are) … does no such thing …. A brief from a broad spectrum of economists argues: Even if the IEEPA permits imposing tariffs (it has never been so used), tariffs would not “deal with” (IEEPA language) trade deficits. Besides, over the past 50 years, in any given year, most countries have run trade deficits …. A brief from the New York University School of Law’s Institute for Policy Integrity stresses the “major questions” doctrine, which protects Congress from having its words twisted to unintended purposes. It holds that Congress does not cryptically delegate enormous powers. Presidents claiming such delegated powers must cite specific congressional language …. A brief by three Cato Institute researchers refutes the extralegal doomsaying the administration uses, perhaps to compensate for the weakness of its legal arguments …. The administration says tariffs imposed under the IEEPA are indispensable for negotiating agreements with trading partners. But since the IEEPA’s 1977 enactment, 14 regional and bilateral agreements have been reached, without any IEEPA tariffs.” “S. Ct. Tariff Case – Separation of Powers.” Washington Post (11.1.25).

Click to access Malawer.Trump,_Courts_and_Congrss_RTD_4.13.25_.pdf

You must be logged in to post a comment.