The issue of U.S. legislation and tariffs is technical and complex. However, it is clear that it is the Congress that has the exclusive authority to regulate international trade — but much authority has been delegated to the president. The issue of national security in trade policy formulation has become the premier issue in trade law today. Combined with the President’s authority in foreign affairs presidential action over international trade has become a lot more complex in recent history. Global rules are still important.

……………………………………………………..

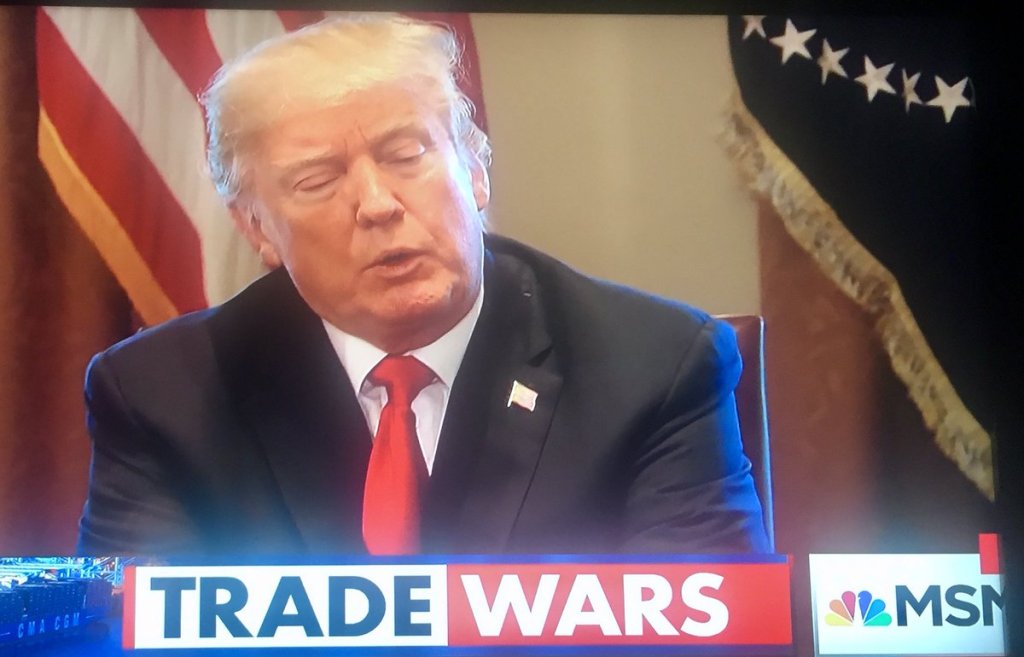

“The US Constitution says very plainly that Congress, not the president, has the authority to impose tariffs. It is there in black and white. Article 1, Section 8: “The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, …To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations.” Congress has not delegated the authority to set the level of tariffs and, what’s more, it is unlikely that it could, under our Constitution, do so. It can delegate selectively, not abdicate its role completely …. Trump and the public became accustomed to him doing what he wanted to do with tariffs during his time in office. In early 2017, on his first day of business after his inauguration, he withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade and tariff agreement with 11 other countries. But that was different. The Congress had not yet approved making the United States a party to that agreement. Later Trump imposed additional tariffs on Chinese imports making the average tariff on goods from China entering the United States over 19 percent compared with imports from other sources averaging 3 percent. He also imposed additional high tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum from all sources. All of Trump’s tariffs, however, as well as those imposed later by President Joseph R. Biden Jr., were put into place under what was claimed to be a delegation of tariff authority to the president from the Congress. Presidents do not have the power to set those tariffs independently …. For his steel and aluminum tariffs, Trump claimed he was authorized to act as the articles in question, steel and aluminum, his administration questionably found, were “being imported into the United States in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair the national security.” This authority was granted by Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. And presidents are granted a lot of leeway in making national security determinations …. For Trump’s China tariffs and Biden’s selective tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, chips, and the like, the authority cited was retaliatory. The president is authorized to impose retaliatory tariffs when “an act, policy, or practice of a foreign country … violates, or is inconsistent with, the provisions of, or otherwise denies benefits to the United States under, any trade agreement, or … is unjustifiable and burdens or restricts United States commerce,” under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. Again, while this was an unprecedentedly wide use of retaliatory authority, a degree of discretion would be allowed a president in administering the law …. Can a broader action be taken under US law? Yes, in an emergency. President Richard M. Nixon put a temporary 10 percent import surcharge (an additional 10 percent tariff) on all imports in 1971. He declared a national emergency, citing a balance of payments crisis (the government was running out of gold to support the gold-backed dollar at the time), and used the Trading with the Enemy Act—a WWI emergency authority created by Congress, to impose this tariff. It lasted four months while new international monetary arrangements were worked out. The courts upheld his use of this authority. However, the courts rejected an alternative claim of authority, to temporarily terminate all trade agreements as needed to impose the tariff. That, the courts said, went too far …. There is authority under Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 in such cases: “Whenever fundamental international payments problems require special import measures to restrict imports—(1) to deal with large and serious United States balance-of-payments deficits, (2) to prevent an imminent and significant depreciation of the dollar in foreign exchange markets,” the president is authorized to impose additional tariffs of up to 15 percent or import quotas for up to 150 days …. Is there any other authority Trump could invoke? The International Economic Emergency Powers Act confers extraordinary authority to the president to block all transactions including imports. The Act says, “Any authority granted to the President by … this title may be exercised to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat … if the President declares a national emergency with respect to such threat.” “Trump’s Tariffs 2.0 and U.S. Trade Law.” Petersen Institute for International Economics (Sept. 2024).

“Over the past decade, there has been a much greater willingness to use tariffs as part of industrial and trade policy. There has also been a parallel emphasis on employing subsidies and other forms of state intervention to boost investment in key sectors. This process is being turbocharged by the way that security issues are becoming entrenched in US government thinking about large segments of the economy, from manufacturing to new technologies. The growing intersection of economic policy and national security has many roots …. Retaining and restoring American manufacturing competitiveness has come to be seen as a defining geopolitical challenge …. concerns become fused in a way that is unrecognizable from the more free market approach that took hold at the end of the cold war …. The role of national security in trade and investment policy and strategy is rising everywhere. There are changes in the way that people are approaching the question of trade policy, international economic policy and that’s true in market economies the world over …. The US appears set on a strategy driven by a combination of China-related security considerations and economic nationalism that will further shake up relations with partners in Europe and the Indo-Pacific …. It is hard to argue that Trump was an “aberration” on US trade policy. “There is a deeper trend under way in the US towards protectionism, and it will continue no matter who wins the election in November.” “National Security and Trade Policy.” Financial Times (Sept. 4, 2024)/

“Global trade now faces its biggest challenge yet, the great-power rivalry between the US and China …. Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles …. As the US-China rivalry intensifies, existing systems of governance are coming under intense strain. Can governments still work together to enforce rules that prevent the system from fragmenting? Or are they actually accelerating it by creating standalone trading blocs? The short answer: probably neither. Multilateralism is weak. The US is undermining the WTO by citing a national security loophole to break rules at will. The EU won a case against Indonesia over its nickel export ban, but the WTO’s dysfunctional dispute settlement system has delayed compliance. But this does not mean regional or geopolitical trading blocs will start setting the rules of trade instead.” “Globalization – Survive?” Financial Times (Sept. 6, 2024)”

You must be logged in to post a comment.